Music

MUSIC

VOLUME TWO BOOK SEVEN

LA MUSIQUE – INTRODUCTION -DEFINITIONS – QUOTATIONS

We all drew on the comfort which is given out by the major works of Mozart, which is as real and material as the warmth given up by a glass of brandy.

Rebecca west (1892-1983), British author. Black lamb and grey falcon. “Serbia” [1942].

Music has charms to soothe a savage breast to soften rocks, or bend a knotted oak.

William Congreve (1670-1729), English dramatist. Almeria, in the mourning bride. Act 1, sc. 1.

Music n.

- The art of arranging sounds in time so as to produce a continuous, unified, and evocative composition, as through melody, harmony, rhythm, and timbre.

- Vocal or instrumental sounds possessing a degree of melody, harmony, or rhythm.

- A. A musical composition. B. The written or printed score for such a composition. C. Such scores considers as a group: we keep our music in a stack near the piano.

- A musical accompaniment.

- A particular category or kind of music.

- An aesthetically pleasing or harmonious sound or combination of sounds: the music of the wind in the pines.

[middle English, from old French musique, from Latin musica, from Greek (Ht) mousikt (Tekhnt), (Art) of the muses, feminine of mousikos, of the muses, from mousa, muse. See men-1 below.]

– the American heritage dictionary

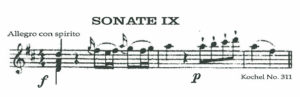

Musical notation, symbols used to make a written record of musical sounds. Boethius applied the first 15 letters of the alphabet to notes in use at the end of the roman period. By the 6th cent. Notation of Gregorian chant was by means of neumes, thought to derive from Greek symbols for pitch (see plainsong); they indicated groupings of sounds to remind a singer of a melody already learned by ear. By the end of the 12th cent. The Benedictine Monk Guido D’Arezzo had perfected the staff, placing letters on certain lines to indicate their pitch. These letters evolved into the clef signs used today. In the 15th cent. The shape of notes became round, and time signatures replaced coloration to indicate note value. The key signature developed early, although sharps were not used until the 17th cent. The five-line staff (with ledger lines used to extend the range) became standard in the 16th cent. Expression signs and Italian phrases to indicate tempo and dynamics came into use in the 17th cent. Notation for electronic music is still not standardized but generally combines traditional symbols with specially adapted rhythm and pitch notation. On notation of lute and keyboard music, see tablature.

– excerpted from the Columbia concise encyclopedia, edition 1995

LA MUSIQUE – INTRODUCTION – DEFINITION

Music (mu ‘zik’), N. [ of. F. Musique, <L. Musica, any art over which the muses presided, esp. Lyric poetry sung to music, music, the art of combining tones or sounds. As of the singing voice or of special instruments (whether by audible execution or by composing and noting), with sweet or agreeable effect to the ear, emotional effectiveness, etc. Or the science concerned with this subject and the principle of melody, harmony, rhythm, etc., involved in it (as, to teach music; the history of music); also, tones or sound so combined, produced by the voice or by instruments (as. “music, when soft voices die, vibrates in the memory,’-Shelley’s “to __ “; “how martial music every bosom warms!” pope’s “ode on St. Cecilia’s day,” III.); hence. Any sweet, pleasing, or harmoniously effective sounds or sound (as, the music of birds, of the wind, or of the waves: the music of the storm: also fig.); something delightful to hear (as, the words were music to our ears); musical, pleasing, or harmoniously effective quality in something heard (as, the music in a voice; “there is … Music in its (the sea’s) roar,” Byron’s “childe Harold,” IV. 178: also fig.); also, tones or sounds suitably combined or arranged, and usually indicated by a special notation, for being rendered by singing or by musical instruments (as, to set words to music); musical work or compositions for singing or playing ( as, a piece of music; to compose music; the music of Wagner; Italian operatic music); the written or printed score of a musical composition, or such scores collectively; also, appreciation of or responsiveness to musical sounds or harmonies (as, “the man that hath no music in himself, nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds, is fit for treasons, stratagems and spoils”: Shakespeare’s “merchant of Venice,” V. I. 83); also, a company of musicians, as a hand (as, “page. The music is come, sir. Pal. Let them play. Play, sirs”: Shakespeare’s “2 henry IV.,” ii. 4.245).

– music drama, an opera in which the musical form is specially adapted to dramatic requirements: applied orig. And specif. To the dramatic type of opera developed by Richard Wagner. See Wagnerism. – music of the spheres, a music, imperceptible to human ears, formerly supposed to be produced by the movements of the spheres or heavenly bodies in accordance with the Pythagorean doctrine of the ‘harmony of the spheres,’ or of the spheres or concentric transparent spherical shells revolving round the earth, in which the older astronomers believed the heavenly bodies to be set (Cf. “and after shewed he him the nyne speres, and after that the melodye herde he that cometh of thiuke speres thryes three”: Chaucer’s “parlement of foules,” 59-61).

Mu-si-cal, A. (of. F. Musical, < ML. Musicalis.) of, pertaining to, or producing music; also, of the nature of or resembling music; melodious; harmonious; sweet or pleasing to the ear; also, set to or accompanied by music (as, a musical comedy); also, fond of or skilled in music. – mu-‘si-cale, N. [ F., fem. of musical.) A social entertainment of a musical character. – adv. – mu’si-cal-ness, N. Music-box, N. A box or case containing an apparatus for producing music mechanically, as by means of a comb-like steel plate with tuned teeth sounded by small pegs or pins in the surface of a revolving cylinder or disk. Music-hall. N. A hall for musical entertainments; esp. A hall or theater for vaudeville, etc. Mu-si-cian, N. (of. F. Musicien.) one skilled in music (as, “the scots are all musicians. Every man you meet plays on the flute, the violin, or violoncello”: also, one who makes music a profession, esp. As a performer on an instrument. A musician: as, “the ·Musicianers amused the retainers. With a tune on the clarionet, fife, or trumpet.” (archaic or prov.)- musl’cianly, a. of or befitting a musician: showing the skill and taste of a good musician. Musiciananship, N. Musicianly skill. Mu-sic-less, a. Without music (as, a musicless entertainment); also, unmusical, or harsh or discordant in sound; also, ignorant of music. Musico -. Form of L. Musicus, pertaining to music, musical, used in combination. – mu-si-co-ora-mat-ic, a. Pertaining to or combining both music and the drama; musical and dramatic musicography – the art of writing down music in suitable characters; musical notation. musi-col’o-gy, systematic study or knowledge of the subject of music, its history, forms, methods, principles, etc. Musi-co-log’i-cal. A. -mu-si-cologist, N. – musicomania n. A mania for music; musical monomania. Musico-phobia n. A morbid dread or dislike of music. Music-room, N. A room, as in a house, set apart or fitted up for use in performing music.

– the new century dictionary 1927

LA MUSIQUE – INTRODUCTION – WRYE HISTORY

Wrye’s embrouillement in tonal intricacies began at probably the late age of eleven when he was planted on a screw-threaded piano stool and screwed up to piano height by a hired piano instructor, a brother-in-law of somebody or other, who inflicted upon him music lessons. After numerous such weekly importunities, Wrye comprehended that his brain would not allow him to concentrate upon two things at once, like left and right hands doing different kinds of stuff on a keyboard simultaneously. From this dour exertion he at least ingested the capacity to instantly recognize the minute and quite subtle differences between the printed half-note and the darker quarter.

Matriculating in the early fall of thirty-seven at a school aptly named highland, as it was located in an area of Louisville at an altitude some forty-feet higher than the rest of the city, Wrye was recruited by the music instructor to join up with his band. He needed and preferred students who could at least read music. He pointed out that some band instruments require only one paw to play.

The French horn sounded sexy, there were only three keys and there was a loaner in stock. Wrye gave it a try – for the first semester.

Wrye was early on unimpressed with, and depressed by, the French horn’s repertoire. It was essentially an excruciatingly repetitive pah!-pah! To the tuba’s oomph!

A second-hand trumpet was acquired and Wrye moved up in the brass hierarchy where melodic action was more rampant.

With conflict of interest trumpet lessons from the school’s band teacher, bond, who was moonlighting way downtown at a downtown musical instrument emporium, Wrye honed his music talents for to become a more brilliant brass-section musician.

The band was strictly a concert band. It played marches and chorales. And simple concert fare re-written especially for school outfits. It never marched about tooting militarily. Its forty to fifty members played for assembly programs, as the pit band for school plays and musicales, and even for parents and teachers nights on rare occasions.

It was probably awful.

Graduating honorably although not quite magna cum laude, from this pseudo-prestigious middle school, Wrye offered his trumpeting talents to the Louisville male high school band – as there were no females, it was so aptly named – in the fall of thirty-nine. He and his non-ambidextrocity had risen to the first chair of the trumpet section in the highlands, but here in the downtown city-wide lowlands he was to start at the bottom of the pack, – of trumpets, that is,

The Louisville male high school concert band boasted some ninety semi-accomplished musicians. The marching band which did parades, and sports events, sported about thirty more. Drums and the such. As the Louisville male high school was a designated an official R.O.T.C. (reserve officers training corps) school, everybody who went to school there (except 4 effs) was furnished by the U.S. Army U.S army uniforms, including the band. This made the L.M.H.S band look rather olive drab at band conventions when bunched together with all the pink, purple, gold, red, white, and blue pom-pommed and tassled clown-suits of all the others. In a world already viciously at war, this olive drab army gear somehow endowed this band of teenagers with an extra aura of martial grandeur, of serious pomposity, and of militant superiority. (out of fear, the band was always rated “superior” by terrified, intimidated judges at all band competitions.) band officers wore sabers. – imagine!

Every morning at seven-thirty A.M. – an hour before the official opening time of school – The full marching band would throw a rehearsal on the adjoining football field and practice its complex halftime maneuvers – many of which Wrye, as the band’s artist, had designed – and its stirring marches, for Friday night’s or Saturday afternoon’s football foolishness.

Wrye got a craw full of band.

At eleven a.m. every day was the concert band hour during which “Rienzi” and “the light cavalry,” and “William tell” and the like were ravaged.

L.M.H.S home game events – football and basketball games always required the racket and excitement of a band. Friday’s full-school assemblies often included music. And then there were evening concerts.

Wrye got a gut full of band.

Wrye, at this exclusive male high ecole militaire, did secure the prestigious first chair solo of the trumpet section – some fifteen strong – and managed to hold that chair against all challengers for his last two years. His brilliance and éclat must have been at least a sharp or flat above the rest – all accomplished brass musicians – it would seem.

As the acknowledged leader of the pack, the honor would fall to him to play, solo, those unsingable high note parts of the star-spangled banner – the national anthem – for the thousands of spectators for those pre-game ceremonies preceding football silliness, for example.

For the reserve officers training corps, he became the official R.O.T.C. bugler, if and whenever an occasion for bugling obtained. The profession of bugling often stood his stead good later in his real military career. There was a genuine dearth of bugle talent worldwide, perks for buglers were undeniably rampant. Wrye practised “reveille,” “to the colors,” first call,” “retreat,” “soupy-soupy,” “taps,” etc. To a fare-the-well perfection. When called upon, Wrye could blow good. And when as a soldier in the army, blow he did, – over here and over there -many, many mornings – “reveille.” – many, many sundowns – “to the colors.” patriotically were sung from the bell of his gilded horn.

Leo Wrye had completed what was known as his secondary education hurdle in the spring of forty-two. He was not yet of conscriptorial age, but close. As colleges were running short of classroom fodder. Rampant volunteerism among patriotic youth at the onset of the great unpleasantness number two was emptying the schools. He was offered a free ride by little centre college in Danville, Ky. By an alumus acquaintance. It seems their pitiful band desperately needed a trumpet player.

He accepted their generosity.

It was a mistake.

As an aetheist he was incompatible.

The band was a miserable group of some twenty teenagers

From all over the state who somehow had been parked, like Wrye, in this goo forsaken Christian [Presbyterian] college for one reason or another. But unlike Wrye they were paying for the parking. Nothing came of the experience but regret. A few attempts to entertain at losing football games were pitiful. Wrye jumped ship in the spring never to play ensemble again.

He was from then but a bugler.

Surviving the great unpleasantness number two, Wrye was euchred into attending the fabulous university of Kentucky at Lexington, for to secure the questionable cachet of a college degree. Whilst so doing he spent a quarter in a required musicology class taught by an antique woman who bored him by playing obscure scratchy pre-unpleasantness recordings.

Wrye’s painting studio was but just one floor above. He arranged with the irritating old lady to pass her examinations, without the benefit of attendance and lectures, by reading the music history book assigned so that he would not interrupt his painting concentration. She agreed – he passed.

It wasn’t until his return to France in nineteen forty-eight that Wrye had any true massive exposure to music. Spending his days mostly in his various Parisian art studios making abstract art was the engaging job at hand. Paris nationale, radio-diffusion franqais had, as did the B.B.C. A “third program” which was a wavelength devoted to all things of cultural stature. The marvellous Paris nationale “troisieme programme” fielded a French musicologist from ten a.m. through two p.m. everyday of the year. He began with the bachs, handel cimabue, vivaldi, etc. And over the next five years must have played and discussed and compared everything ever recorded by each and every great classical composer down through Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. After which time Wrye had sailed off. Returning to L’Amerique.

Fortunately, the Louisville Kentucky free public library shortly precedent to Wrye’s return had established WFPK, a classical music frequency modulated (FM) radio station, which presented Wrye with the opportunity to continue his informal immersion in the art of classical music. With the library’s weekly detailed program of music at hand and the appearance of high fidelity audio-cassette recording equipment, capturing and comparing and collecting specific concert reproductions of specific artist, composers and orchestras from the WFPK tower was an incredible opportunity.

Wrye eventually understood that Wolfgang was supreme, and eschewing all others, built a collection of Mozart’s creation of great variety and depth. (see chapter two b – the Mozart audio library.

LA MUSIQUE – EN RETROSPECTIVE

As testified to’ by the allotted preceding twenty-nine pages given over to the practice of sawing on, beating on, blowing on, tooting on, strumming on, plucking on, and pounding on various peculiar devices, and to his serious harkening unto the gamut of noises so produced, variously, it could be written that Wrye had been somewhat thoroughly exposed to la musique out there, down through the ages, – his and its.

After seventy some years of admitted third-hand interest in this noisy ancient art form, – third-hand interest to Wrye, after his putting music after in preference to the writing arts, – he naturally relegated these both to playing second cellos, so to speak, to his prime focus, the visual arts.

This said, Wrye would also clarify his position vis a vis music and everything else out there which has the effrontery to affront the sense organs of his sentient being, over time and through space.

Wrye had long maintained that human life is essentially a process of constant evaluation and re-evaluation, and re-evaluation, – evaluations of things and events of very slight imposition, of things and events of seemingly monumental importance, events and things understood, misunderstood and even at times misinterpreted.

This being accepted, it would be seen that evaluation of and response to such relativistic subjective events as the arts, over time, would be forcibly subjectively relativistically in continual evaluation.

So it had been with Wrye, vis a vis la musique.

Wrye, and probably not just a few others, have been so awash in so much music in the past decades, courtesy of Thos. Alva Edison, and others, that being driven to a re-examination and a reconsideration of la musique would not be considered exceptionally exceptional.

Wrye’s professional involvement with La musique had not been primarily one of embracing its lilting raptures for their soporific transport, but more of an interested seeking out of the complex aesthetic relationships which the abstract visual and abstract musical arts might have discovered to be common to or similar in, each.

Wrye’s research and his past acquaintance with the corpus of “western music” would inevitably find most of the existing repertoire pitiable in its paucity of truly creative imagination. Slavish reproductions tied to gee-whiz virtuosi, unashamedly tiresome repetitions of their own or borrowed themes, figures, phrases, and whole pages of uninspired pedestrian notes for the want of knowing what to do next. Romantic militarism, bucolic musings, bombastic posing, childish balletic prancing about nonsense, not to mention the morbid religious panderings of some, encouraged Wrye little in the quest of discovering an aesthetic in music which could complement that of the visual arts.

but then there was Wolfgang

In the music of Mozart Wrye found the ultimate paradigm, – a surpassingly subtle creative talent lavishing from within his creations exquisite imaginative delights of form and fancy and fascination, – creations built with precision, astute inventive flair, and in most wondrous variation, – filled with surprise and melodic beauty, – deeply rich and always subtly surprising compositions – musical transcendencies, awash in the musical depth of Mozartian light, color, and joy.

Wrye in his later years admitted readily that he could stand to listen to very little musique other than that of little herr wolfgang amadeus; some chopin, very few of pompous Ludwig’s tirades. Eric Satie fascinated Wrye on rare occasion, but, then, Satie is a rare occasion.

As background music, silence became the preference of Wrye. Silence was always preferable to even Mozart, when Wrye was labouring seriously in the fields of the visual.

The polyglot musical fare of the ubiquitous “classical music stations,” by the end of the century, in their round-the-clock culture initiative, delivered way far too much repetitive ancient mediocrity for Wrye’s elevated taste.