Leo Wrye Zimmerman (1924 – 2008)

Introduction

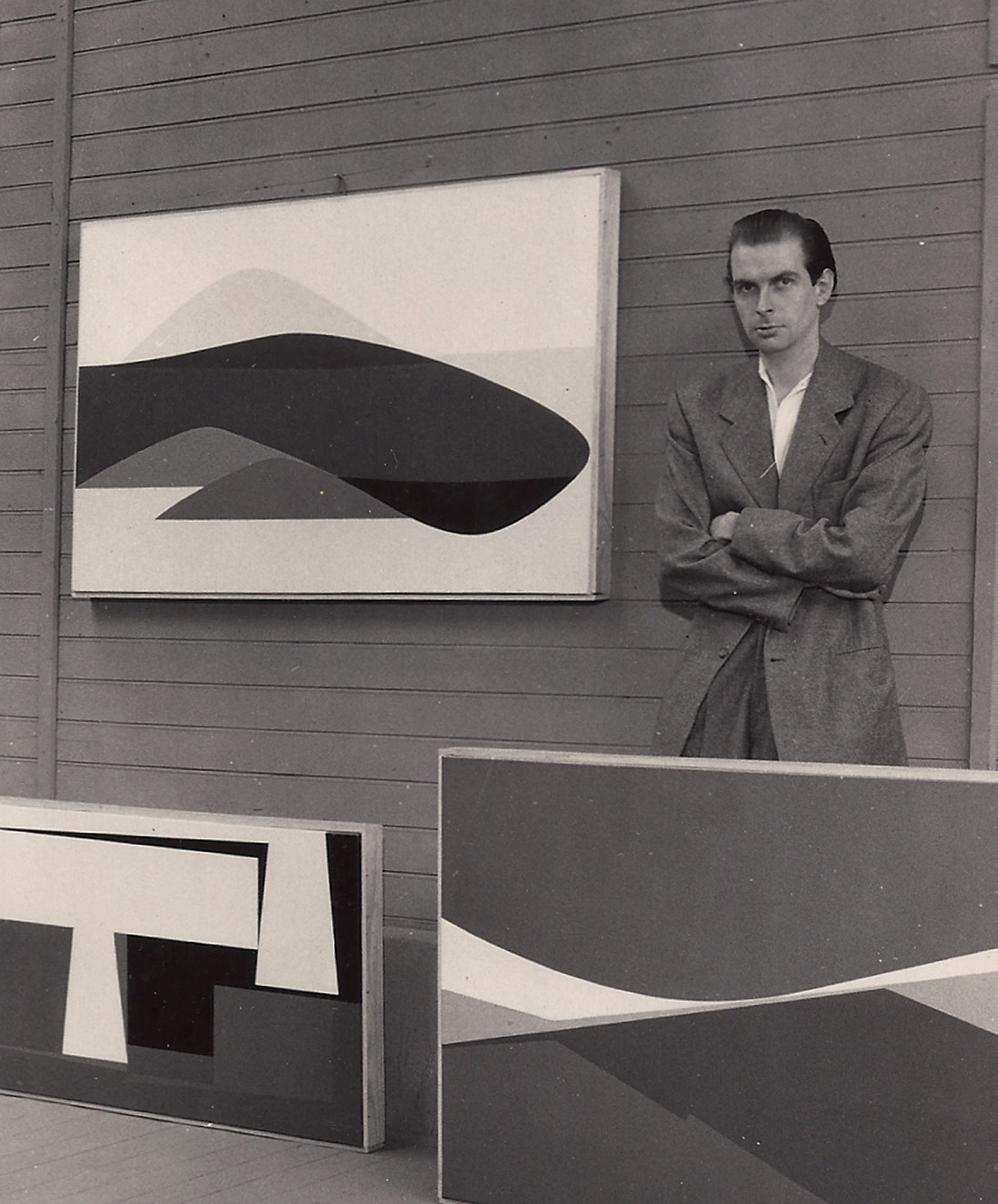

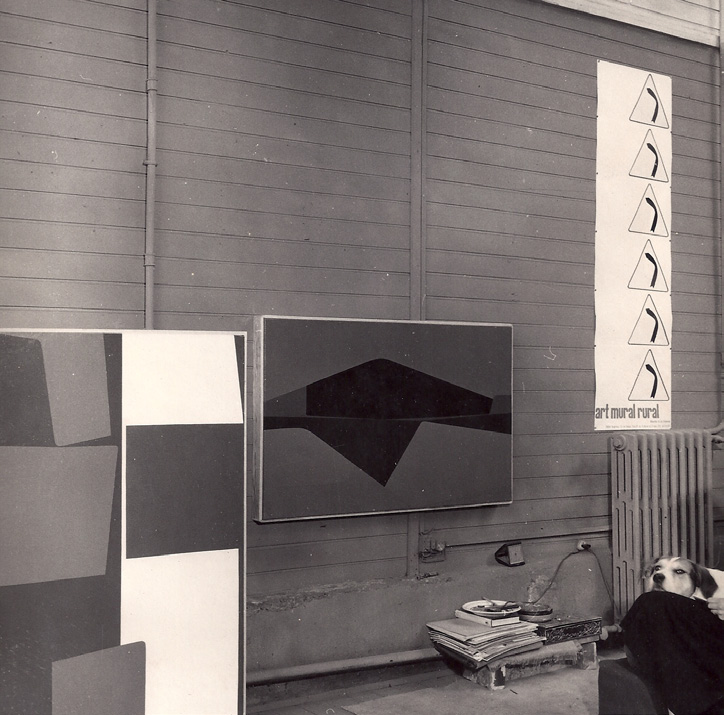

Intralocke (#14), oil on canvas, 1952

In April of 2008, Leo Zimmerman passed away. It had been nearly two decades since his last public show, but his studio in Old Louisville revealed a man busily toiling away, tirelessly charting the progress of an ever-evolving visual manifesto. Years of exploration in the field of geometric abstraction was informed by Zimmerman’s diverse array of endeavors in typography, mechanics, graphic design and entrepreneurship. The resulting artistic style synthesized the aesthetic of non-representational, hard-edged shapes and aggressive color with a philosophy of invention. Zimmerman, who later took up the pseudonym Leo Wrye as a reference to both a favorite drink and his own contrary sense of humor, felt art was vital to the well being of societies. After returning from Paris in the 1950’s he spent years invigorating the local arts community, helping to instigate what was hailed as a cultural renaissance for Louisville, before dropping out of the pubic spotlight entirely. Even during his reclusive years, his orientation towards process compelled him to create prolifically, pressing ever forwards towards new ground. Yet, instead of embracing the final products of his efforts as a prized artifact of artistry or invention, Zimmerman regarded these works as byproducts of discovery. But for viewers, they are road maps to self-realization; a carefully demarcated atlas to help unravel our own journey of seeing.

Early Biographical Information

Leo Zimmerman was born in Timlin, Pennsylvania on September 21, 1924, but moved to his mother’s hometown of Louisville, Kentucky by the time he was five years old. After graduating from Male High School, he enrolled at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, where he would ultimately volunteer for the army at the draft board in April of 1943. For two years and fifty-two days, Wrye served in what he called “that great unpleasantness number two” (WWII), before being honorably discharged on VE-Day at Camp Atterbury, Indiana. Interestingly enough, Zimmerman’s original plan had been to study medicine and follow in his father’s footsteps, however it would be during his time in the army that he would first be exposed to formal art training at the Biarritz American University in France. Upon his return to the U.S., Zimmerman enrolled at the University of Kentucky and majored in fine arts.

The Paris Years

After receiving a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from the University of Kentucky in 1948, Zimmerman returned to Louisville and entered a painting in the “Annual Kentucky and Southern Indiana Exhibition of Art” at Stewart Dry Goods Store. The exhibition was judged that year by Katherine Kuh, curator of art interpretation for the galleries at the Art Institute of Chicago. She rewarded Zimmerman with first place for his painting Main St. Façade, which he described in the April 22, 1948 issue of the Courier Journal as “an abstract with a realistic subject.” The painting was a formalized vision of main street buildings with several storefronts and a bright red lamppost. The prize money would allow Zimmerman to travel back to Paris, France, a thriving locus of artistic development after WWII.

Joseph Fitzpatrick, who would later work alongside Zimmerman on Arts in Louisville, recalled in an interview, how he saw Leo for the first time in years at the Air Devils Inn just prior to his return to France in 1948. The two shared several things in common; Fitzpatrick had also served in the military, each had been accepted into the “Annual Exhibition of Art” and both young American veterans were on their way to Paris, France to study art. The two remained in touch during their time over seas.

Fitzpatrick described Zimmerman’s work ethic during his years in France as admirable, diligently striving to produce a painting a week. During a visit to a gallery in Paris, Zimmerman and Fitzpatrick had their initial exposure to avant-garde art, and since France had been always been a leader in setting new styles, they were both eager to be involved. They knocked on the door of abstract artist and secretary general of art at the Atelier D’Art Abstrait, Edgard Pillet, who would welcome them and act as a mentor and artistic collaborator. Later, Pillet would serve as an advisor and contributor to Zimmerman’s publication, the Arts in Louisville during a stint as artist in residence at the University of Louisville.

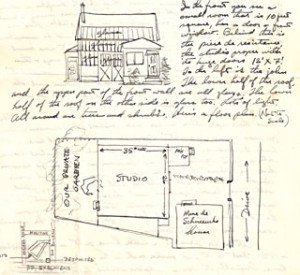

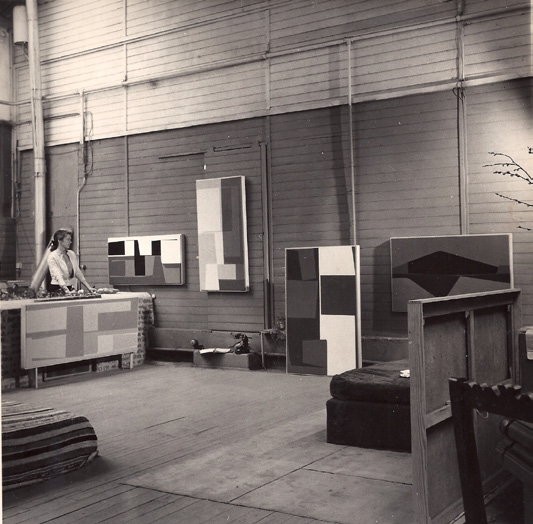

Paris Studio, 1953

(Marie Zimmerman standing)

While in France, Zimmerman would also be invited to join La Groupe Espace, an association founded in Paris in 1951 by André Bloc and artists affiliated with the periodical Art d’aujourd’hui. He would mix with artists such as Victor Vasarely, Jack Youngerman, Ellsworth Kelly and close friend, filmmaker Robert Breer.

In a letter to his parents dated February 16, 1953, Zimmerman describes his invitation to be part of La Groupe Espace, saying, “Pillet and Bloc… have ask me to become the American manager of [Art d’aujourd’hui] subscriptions in USA to spread the good word. Also they have invited me to join a group of Artists, Architects and decorators who call themselves La Groupe Espace. They want me to help establish an American branch. There exist in Belgium, Sweden, Denmark, and Holland already branch groups. The purpose is to foster closer cooperation between the various plasticiens.” In a later letter, dated March 11, 1953 Zimmerman describes the group’s purpose in more detail, “The Groupe Espace is an organization of artists and architects who are trying through common effort to bring a little closer relationship between the arts and their relation to la vie”

In order to supplement the allowance provided by the G.I. bill, Zimmerman took an entrepreneurial leap and began selling popcorn to the Paris public who were unfamiliar with the white morsels of crispy cooked kernels. Alongside Edgard Pillet, Zimmerman distributed his wares from the back of a beloved but dilapidated English pick-up truck to bars and grocery stands throughout the city. By July of 1950, Zimmerman was selling about 2000 bags of popcorn a week for 25 francs a piece- or seven cents American—with a gross sales profit of about $140 dollars a week (A Wrye Life, v1 b3 ch1 pg 6b, AP, 1950). Zimmerman also designed a sidewalk popcorn machine (which he convinced a French firm to manufacture), an industrial size popper and a bag sealer, the latter two of which were installed in an abandoned sculpture studio that doubled as the young artist’s make shift popcorn factory. Popcorn sales made it possible for Zimmerman to continue living and studying art in France without compromising his ideals saying, “I don’t hope to make a living at painting. You have to get into the schmook clique to do that. And I would rather paint for art than for people who like art because they think they ought to. I’ll keep on painting for art and make my living selling popcorn”. However, between the red tape involved in importing the un-popped kernels from Davenport, Iowa and difficulty with vendors stealing the profits, the operation eventually shut down. The old English pick up truck, which had hauled the popcorn, was sold to Victor Vararely for one hundred dollars worth of francs.

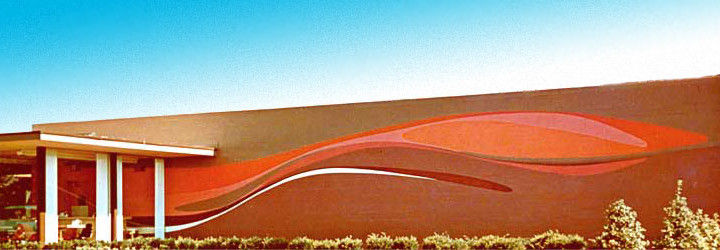

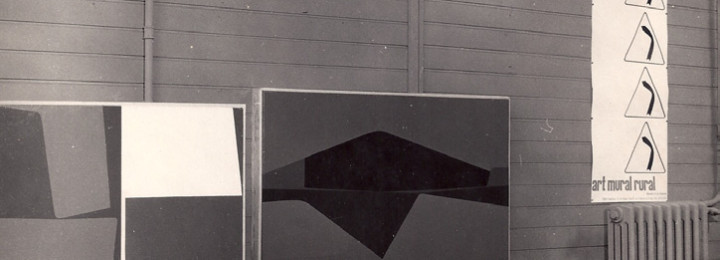

Rural-Mural

The rural-mural was an idea originally conceived by Zimmerman in 1952 after spending time driving through the countryside of France. It combines his aesthetic of geometric abstraction, aggressive color palette and sense of visual drama with his philosophy that art should be available to the public, enrich their experience and enhance the beauty of public visual space.

The excerpt below, from a letter dated March 11, 1953, is a translation of the text on the invitation to Zimmerman’s Paris studio show of paintings. Composed by a French writer identified only as Alvard, it describes the concept for Zimmerman’s Rural Murals.

“Z. knows the dangers of publicity and the servitude that it can impose. But there is not adventure without danger. There exists along the highways great surfaces given over to the most mediocre usage of advertising which awaken the desire to make them serve more noble usages, and who knows maybe reconcile the natural beauty of the landscape that surrounds them. Zim. takes the problem in reverse. He reacts against the slavery of publicity in the hope to put, for one time, money at the service of art. What one sees on the walls on his studio it must be underlined are paintings, which if they are destined to be considerably enlarged demand to be judged as paintings. He has simply hunted for simple abstract forms to facilitate their reproduction but without sacrificing anything of their subtlety and their personality. As for the colors, they owe nothing to anything except the interior exigencies of the painter”

The rural-mural concept was articulated in a letter to his parents. January 21, 1952. Zimmerman writes, “There has been a lot of discussion on the subject of easel painting; its purpose, dissemination, and future. There are those who contend that the easel picture (that is as opposed to the mural painter) shall continue to exist in its present role, being shown in gal[l]eries, sold to collectioners, and museums, and being a possession of someone or a few for their individual pleasure. There is the opposing view toward easel painting which feels that the future of easel painting is very precarious. This form of art does not reach enough people to be effective as an art form, has too limited means and market to be a financial success, and is therefore doomed to a limited and precious existence…

“I suppose that you are asking me why I put all this emphasis on the importance of the presence of good form (in the general sense meaning shapes, colors, materials etc which are employed with the best of taste). I feel that good form is an absolute necessity in the psychological well being of the human being. You have heard of the results of experiments in industry on production by which the painting of a factory interior in more pleasant tones augmented production. This is one of the more simple effects of form on man. Environment plays a huge role in the psychic formation of a man’s character. The presence of art, whether it be music, architecture, sculpture or painting does have a very important effect also as a part of man’s env[iro]nment. But it is obviously ineffectual if it is seen only rarely, and then only when sought by those who feel the need. Good form is a spiritual food that is as necessary to the [spirit] as potatoes to the stomach. Those who are deprived of it are starving… You have gathered that I was planning to make some liaison between fine arts and commerce. This liaison takes the rather peculiar form of mural painting as a commercial art, advertising a product. But I feel that only [through] mural art can any number of people be affected. And here hangs the tail.

“Rural-Mural Barn painting: You know of course that there are several companies who find it efficace to advertise their products on the side of a barn, the whole side of the barn. Main Pouch, Bull Durham, Jefferson Island Salt. These ads are only ugly colored letters giving the name of the product. They are peut-être effective as ads, but a blight to the landscape. I have hit upon the marvelous idea of utilizing these huge surfaces for art. And art which will serve the second purpose as advertising”

In the November 1956 issue of Arts in Louisville, Zimmerman was able to announce that his vision for the rural-mural would come to life—only in a more urban environment, “On Shelbyville Road about one mile this side of the Watterson Expressway” at a drive-in restaurant owned by patron of the arts, Austin Pryor. Louisville architect, Norman Sweet designed the drive-in’s building and called Zimmerman with Pryor’s request, “Could a rural mural become suburban?”

Zimmmerman acquiesced and when completed, the mural was sixty-seven feet long and thirteen feet tall. “I hope that this mural becomes more than a source of shock to the 45,000 or so daily passers-before-it; that it becomes an added excitement in the landscape; that it bring[s] to those who pass a response of individual signification in this vast, exuberant, unwieldy, unsettling, modern human extravaganza”, Zimmerman wrote in Arts in Louisville. Pryor would also commission Zimmerman to design a forty-foot tall rotating hamburger sculpture for the restaurant. For five years the mural graced the wall of the drive-on on U.S. 60 until a later expansion of the building obscured the mural from view.

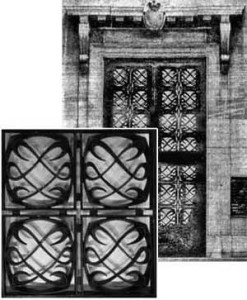

Library Doors

By the mid-sixties Zimmerman had dropped out of the public art scene, though he continued to stay creatively active working independently and collaborating with other local artists. He was hired on as the physical facilities manager at the Louisville Free Public Library in 1966 where he worked until 1977. During his time working as physical facilities manager Zimmerman worked alongside prominent Louisville sculptor, Barney Bright to produce a set of cast aluminum door panels for the Main Branch of the Louisville Public Library at 301 York Street. The doors, which were designed by Zimmerman and sculpted by Bright, were composed of 32 panels, each baring the double “L” emblem that the library used in their seal. The doors were installed at the library’s south entrance from 1970 until their removal in 1993 when renovations were done to the York Street building.

Inventions

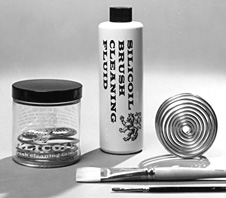

In 1954, dissatisfied with the available brush cleaning systems that incurred damage to paintbrushes during washing, Zimmerman developed an alternative device he named “the Silicoil”. The invention of the Silicoil brush cleaning system was patented in 1962 and afforded Zimmerman the freedom to focus on pursuing his artistic vision. The Silicoil, manufactured and distributed by the Lion Company, Inc. in Louisville, Kentucky, continues to be one of the leading brush cleaning systems on the market today. Its design is one variation of the swirling, spinning, rotating movements Zimmerman frequently used to explore relationships between forms. It is these series of concentric circles, manifested three dimensionally in the elegant utility of the Silicoil, repeated in paintings such as Double Coil and Untitled #9 and evident in the rotating motion of the Slu Balls that thematically unites Zimmerman’s visual vocabulary.

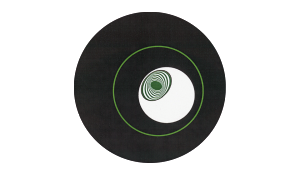

Slu Balls

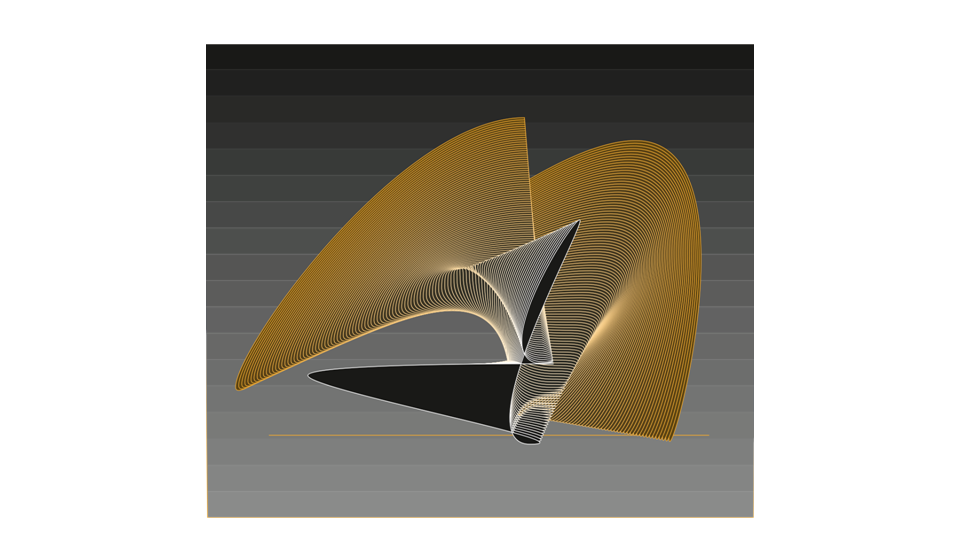

The Slu Balls (also spelled “Slue”), or Lacquered Kinetic Paintings, were first exhibited at the University of Kentucky in 1989. Zimmerman believed that “painting is essentially an astonishing art of illusion” and these paintings represent Zimmerman’s explorations in kinetic or moving/shifting perspective. Through combining elements of hard-edged geometric shapes with mechanical savvy, the artist creates an “illusion and a unique aesthetic experience” (Press Release, 1989). The kinetic paintings are fabricated from aluminum sheets that have been lacquered, inlaid and mounted on a lacquered aluminum panel. Behind this, an electrical motor powers the turntable, which creates the motion necessary for the illusion held within the walnut frame. When the motorized turntable  begins its revolution, the elliptical discs within the panel appear to “move not in a circle, but in and out and back and forth through space” in a surprising display of optical trickery (Press Release, 1989). Zimmerman fabricated a total of twelve Slu Balls in a demonstration of the variety and potential to be found in the relationship between forms. He averred that, “Seeing, itself, is illusory. Perception is an intricate, complex process of integrating and interpreting visual experience. These paintings astonish via that process” (Wrye Artist Statement, 1989)

begins its revolution, the elliptical discs within the panel appear to “move not in a circle, but in and out and back and forth through space” in a surprising display of optical trickery (Press Release, 1989). Zimmerman fabricated a total of twelve Slu Balls in a demonstration of the variety and potential to be found in the relationship between forms. He averred that, “Seeing, itself, is illusory. Perception is an intricate, complex process of integrating and interpreting visual experience. These paintings astonish via that process” (Wrye Artist Statement, 1989)

Slu Cube

In 1992, only several years after the show of Lacquered Kinetic Paintings debuted at the University of Kentucky, Zimmerman added another creation to his arsenal of “illusion-works”. He deemed it the Slu Cube. Developed using a 3-D drawing program on an Apple Macintosh Quadra 700 computer, the slu cube structure is composed of three panels joined together to form a single inside corner with printed design elements fixed to its inner walls. In A Wrye Life Zimmerman provides detailed directions on how to reproduce the optical effects on a Macintosh computer but notes that given the rapid advances in computing his instructions will quickly be outdated, in lieu of more advanced technologies.

Apple Art

Deemed “Apple Art” because of their production on an Apple Macintosh Quadra 700, these abstract vector illustrations exhibit qualities found in Zimmerman’s earlier work, but with the added dimension of time and motion. Created beginning in 1992 using a basic graphics program called Aldus Freehand Version 3.1 and a digitalizing tablet, Zimmerman creates forms that unfurl and evolve dynamically. Zimmerman saw the vast potential for digital drawing technology very early in its development and quickly adopted it as a medium for artwork. More than twenty-five “Apple Art” paintings are documented in Zimmerman’s book, A Wrye Life, and according to friends and family he created approximately 2,000 in the years before his death.

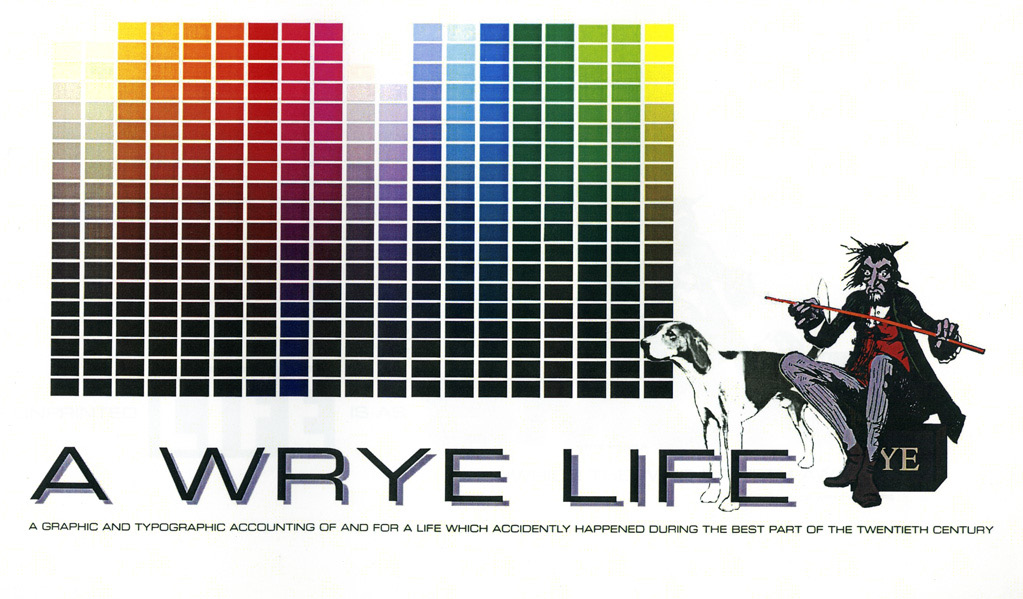

A Wrye Life Book

In 1993 Zimmerman began work on an autobiography. The book, which he titled, A Wrye Life, grew to over 1,300 pages before its completion and in addition to his art covers his life and his interest in all things mechanical including power and painting tools. Hound dogs, Mozart, custon built automobiles and hundreds of Wrye aphorisms are detailed and illustrated. The book was supposedly written and edited by close friend, Jean Phillipe Le-Seigleur. Zimmerman attests that fictional author Le-Seigleur, whose background was in engineering, became interested in the “Apple Art” during its development and set out to produce a book that would serve as a biography, philosophy, gallery and comprehensive archive chronicling Zimmerman’s life. Though mostly accurate in its account of Zimmerman’s artistic career, the book does take certain liberties with the truth, acting as a creative reconstruction of this artist’s very wry life.

A Wrye Vision: Arts Importance in Society

“I believe that art (painting, music, sculpture, and literature) is the most important manifestation of human culture. It is art, ‘the finer things of life’, that makes any human activity seem worthwhile. It is through the cultural heritage of the past (that) today’s man thinks himself as a civilized being… There must be art, no culture has ever existed without it that has deserved to be called a civilization. There must be art, and to make arts there must be artists… I feel that art in galleries is lost to many people who would benefit otherwise if they could be induced to consider art as one of the basic elements of all societies.”

– Zimmerman in a letter to his parents from Paris, France, March 18, 1952